Last month I left Santa Fe and moved to Providence, Rhode Island. I'd spent almost five years in Santa Fe and loved a lot about the city--there were other things I liked less. I loved the mountains and the sunsets and my friends in Santa Fe; the state government, the lack of customer service attitude, the problems with the educational system, the drought and thunderstorms--not so much.

A variety of reasons coalesced to persuade me to move back East--among them the fact that I turn out to be a city gal at heart. I didn't think I missed the green and the ocean until I got back here and realized how much. And there's an East Coast attitude that it's hard to define but, as Justice Potter Stewart famously said about pornography in 1964, "I know it when I see it." In addition, I'm working on a book about Boston in 1905--you can read about my observations on that year in my Boston 1905 blog. You can find the link on the upper right of this page, along with a link to my new Providence blog.

Thanks for being my readers!!!

Choosing Santa Fe

Observations about Santa Fe life, art, culture, and history with occasional other musings.

Sunday, July 17, 2011

Monday, January 24, 2011

A Plethora of Chile

If you go into a grocery store in some other part of the country, you'll see a few linear feet of shelf space in the "ethnic foods" aisle dedicated to Hispanic foods. A few kinds of chiles, salsa, taco shells, etc. In the big chain groceries in Santa Fe, there is typically an entire aisle dedicated to Hispanic foods. Of course, this ends up taking the space of other products--so there is usually a much smaller selection of canned mushrooms, chutney, water chestnuts, etc.

The Hispanic food aisle in the Santa Fe Albertson's makes me feel like Robin Williams in Moscow on the Hudson, where the Russian immigrant he plays faints in the coffee aisle--overcome by the sight and smell of so many different kinds of coffee. No fainting here--but an overwhelming set of choices!!

Sunday, November 07, 2010

New Mexico History Museum

I toured the new New Mexico History Museum in Santa Fe this week--what a terrific museum! Lots of interesting exhibits, clear and easy to follow history, and an established route through the museum that means you can pay attention to the displays instead of wondering where to go next. I had seen a lot of the material when it was in the smaller exhibit space in the Palace of the Governors, but there is so much more to see in the new space. It uses a lot of new thinking in museum design--audio and video displays, tactile exhibits, and comparative timelines.

There were many things I liked in this museum but the exhibit I wanted to share with you today is a sterling silver cigar humidor that's a model of the Taos Pueblo. It was manufactured in 1917 by Tiffany--part of a 56-piece set made for the ward room of the battleship USS New Mexico. It's just so beautiful!

The photo below, from 1919, shows the table and sideboard in the USS New Mexico ward room set with silver pieces from the collection.

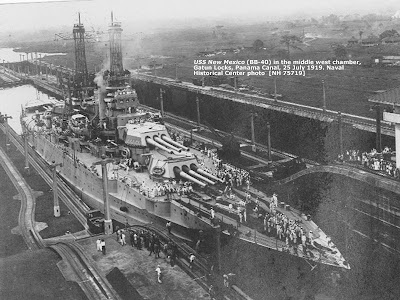

And here is the ship itself, at the Panama Canal in 1919.

Illustration Credits and References

The wardroom photo was published in 1919 by A.M. Simon, 324 E. 23rd St., New York City, as one of ten photographs in a "Souvenir Folder" of views concerning New Mexico. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph # NH 105048. Donation of Edwin C. Finney, Jr., 2007, from the collection of J. Louise Finney.

The photo of the battleship USS New Mexico, Official U.S. Navy Photograph, USNHC # NH 75719, now in the collections of the National Archives.

There were many things I liked in this museum but the exhibit I wanted to share with you today is a sterling silver cigar humidor that's a model of the Taos Pueblo. It was manufactured in 1917 by Tiffany--part of a 56-piece set made for the ward room of the battleship USS New Mexico. It's just so beautiful!

The photo below, from 1919, shows the table and sideboard in the USS New Mexico ward room set with silver pieces from the collection.

And here is the ship itself, at the Panama Canal in 1919.

Illustration Credits and References

The wardroom photo was published in 1919 by A.M. Simon, 324 E. 23rd St., New York City, as one of ten photographs in a "Souvenir Folder" of views concerning New Mexico. U.S. Naval Historical Center Photograph # NH 105048. Donation of Edwin C. Finney, Jr., 2007, from the collection of J. Louise Finney.

The photo of the battleship USS New Mexico, Official U.S. Navy Photograph, USNHC # NH 75719, now in the collections of the National Archives.

Sunday, October 31, 2010

The Harvey Girls

I just finished reading The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West by Lesley Poling-Kempes. It shed light for me on a whole aspect of Southwestern history that I didn't know very much about, and I thought some of the key points were worth mentioning here.

I just finished reading The Harvey Girls: Women Who Opened the West by Lesley Poling-Kempes. It shed light for me on a whole aspect of Southwestern history that I didn't know very much about, and I thought some of the key points were worth mentioning here.After the Civil War, the Atchison, Topeka, & Santa Fe laid railroad tracks from Kansas to Colorado (1872), through Raton Pass to New Mexico (1878), into Lamy (the nearest stop to Santa Fe, 1880), and finally to California (1887).

As the trains began carrying passengers, the railroad built depots every 100 miles or so. There were no dining facilities on the trains and meals from home only lasted so long! Fred Harvey, a Londoner who had emigrated to the US at the age of 15, was a former café owner and a veteran clerk and agent for the railway, and was in the right place at the right time to start a train-oriented food business. The railroad he worked for (Chicago, Burlington, & Quincy) did not think much of his idea of restaurants at the various rail stops heading west, and they told him to go to the Atchison, Topeka, & SF because they "would try anything".

It's the same old story of start-ups being hungrier and more creative than the old, established, and more complacent businesses, and saying "yes" to Harvey turned out to be a brilliant marketing move on the part of the new railroad. Under their agreement, the RR provided depot space, coal, ice, water, and transportation, and Harvey provided food and staff. Harvey opened his first restaurant in Topeka in 1876, and his businesses spread southwest and west in parallel with the expansion of the railroad.

Harvey had exacting standards for his restaurants (and later the hotels that accompanied them). They provided elegant menus, an unparalleled choice of foods from all over the continent (brought in daily by train), white tablecloths and napkins, and split-second timing. (Telegrams would notify a restaurant of the precise time of the next train arrival, and of certain choices on the part of the passenger-diners.) Everybody had to be in and out--perfectly served and catered to--in 30 minutes. The restaurants gave the AT & SF a unique competitive advantage.

In the beginning, Harvey used male waiters in the restaurants. But in 1883 he fired all the waiters at his Raton, NM Harvey House because of poor service the day after a midnight brawl. It was suggested to Harvey that women might do a better job because they were less likely "to get likkered up and go on tears." The new waitresses were so popular that Harvey decided to replace all of the waiters in his establishments with waitresses, and he advertised in midwestern and eastern newspapers for "young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent" to go west to work.

In the beginning, Harvey used male waiters in the restaurants. But in 1883 he fired all the waiters at his Raton, NM Harvey House because of poor service the day after a midnight brawl. It was suggested to Harvey that women might do a better job because they were less likely "to get likkered up and go on tears." The new waitresses were so popular that Harvey decided to replace all of the waiters in his establishments with waitresses, and he advertised in midwestern and eastern newspapers for "young women 18 to 30 years of age, of good character, attractive and intelligent" to go west to work.Over 100,000 women served as Harvey Girls from 1883 until the 1960s. For many of these small-town girls and farmers' daughters, the Harvey establishments provided the college education they could not afford--a chance to travel, meet people they would never have had a chance to meet, broaden their horizons, live in a dorm with other young women, and find a husband in the male-dominated west. While many young women worked for a year or two and then returned home, many others moved from community to community over the years--sampling life in many different parts of the country. Thousands of Harvey Girls met and married Santa Fe railmen, cowboys, ranchers, and the occasional other Harvey employee (in spite of restrictions against dating within the business). They and their husbands became the founding mothers and fathers of many towns in the Southwest. (Will Rogers said of Fred Harvey and the Harvey Girls that they had "kept the West supplied with food and wives.")

The Harvey Girls had to adhere to a tough schedule and many rules governing their dress and behavior. They wore black uniforms and freshly starched white aprons and were thoroughly trained in service standards before being let loose on the floor. They were paid competitive wages, and since they were provided with room and board most were able to save or send home a substantial amount of money.

In many parts of the country, waitresses were considered to be barely a step above prostitutes, and Harvey's strictness helped to preserve the girls' reputations. However, they were more socially accepted in some communities than in others.

Harvey Girls had many opportunities that were unique for women at the time. The company instituted an early form of job sharing--where farmgirls were allowed to go home in the summer to help with the harvest, and Eastern schoolteachers worked in their place on their summer vacations. Girls in communities with colleges (such as Albuquerque and Las Vegas, NM) could wrap part-time work schedules and part-time college classes together.

In its heyday (roughly 1910-1940), the Fred Harvey Company operated a dozen or so hotels, 50-60 dining rooms and lunchrooms, and 60-100 dining cars on trains.

New Mexico was a particularly successful area for the Harvey Company. There were 16 Harvey Houses in New Mexico at the peak of the business--including some of the grandest in the country. These included the Montezuma and the Castañeda in Las Vegas, La Fonda in Santa Fe, the Alvarado in Albuquerque, and El Navajo in Gallup. (NOTE: The Alvarado and the El Navajo were eventually torn down. The Montezuma is now United World College, the Castañeda is privately owned, and the La Fonda has continued to operate as a very successful hotel and restaurant. In fact, my book club, which selected and discussed this book in October, met at the La Fonda for dinner and our discussion--to put ourselves in the right Harvey Girl mood!)

New Mexico was a particularly successful area for the Harvey Company. There were 16 Harvey Houses in New Mexico at the peak of the business--including some of the grandest in the country. These included the Montezuma and the Castañeda in Las Vegas, La Fonda in Santa Fe, the Alvarado in Albuquerque, and El Navajo in Gallup. (NOTE: The Alvarado and the El Navajo were eventually torn down. The Montezuma is now United World College, the Castañeda is privately owned, and the La Fonda has continued to operate as a very successful hotel and restaurant. In fact, my book club, which selected and discussed this book in October, met at the La Fonda for dinner and our discussion--to put ourselves in the right Harvey Girl mood!)

New Mexico was a particularly successful area for the Harvey Company. There were 16 Harvey Houses in New Mexico at the peak of the business--including some of the grandest in the country. These included the Montezuma and the Castañeda in Las Vegas, La Fonda in Santa Fe, the Alvarado in Albuquerque, and El Navajo in Gallup. (NOTE: The Alvarado and the El Navajo were eventually torn down. The Montezuma is now United World College, the Castañeda is privately owned, and the La Fonda has continued to operate as a very successful hotel and restaurant. In fact, my book club, which selected and discussed this book in October, met at the La Fonda for dinner and our discussion--to put ourselves in the right Harvey Girl mood!)

New Mexico was a particularly successful area for the Harvey Company. There were 16 Harvey Houses in New Mexico at the peak of the business--including some of the grandest in the country. These included the Montezuma and the Castañeda in Las Vegas, La Fonda in Santa Fe, the Alvarado in Albuquerque, and El Navajo in Gallup. (NOTE: The Alvarado and the El Navajo were eventually torn down. The Montezuma is now United World College, the Castañeda is privately owned, and the La Fonda has continued to operate as a very successful hotel and restaurant. In fact, my book club, which selected and discussed this book in October, met at the La Fonda for dinner and our discussion--to put ourselves in the right Harvey Girl mood!)In many towns, the Harvey House became the center of local social life. It was usually the best and most elegant restaurant in town, and movie stars, presidents, and other luminaries were often spotted there on their way across the country by train.

The Harvey Company was run by Fred Harvey until his death in 1901, and after that by his son and grandsons.

Eventually, the Harvey Company fell victim to changing times, particularly the growth of auto and air travel. During the second world war, the company devoted a huge portion of its business to providing meals to troop trains as they traveled across the country, but the pressures of serving thousands of servicemen caused service levels to deterioriate and local community customers to receive short shrift. Many food were no longer available due to rationing, and there was no time to adequately train the increased staff needed.

Beginning in the 1930s, the Harvey Company had also expanded into large US train stations (Chicago and San Diego), bus terminals (San Francisco), and airports (Albuquerque). From about 1959 to about 1975, Harvey operated a series of restaurants along the Illinois Tollway.

The original Fred Harvey Company lasted until 1968 when it was purchased by the Amfac Corporation of Hawaii. Amfac was renamed Xanterra Parks & Resorts in 2002. In 2006, Xanterra purchased the Grand Canyon Railway and its properties, including the Grand Canyon Hotel. So now the reincarnation of the Harvey Company is operating a railroad!

The original Fred Harvey Company lasted until 1968 when it was purchased by the Amfac Corporation of Hawaii. Amfac was renamed Xanterra Parks & Resorts in 2002. In 2006, Xanterra purchased the Grand Canyon Railway and its properties, including the Grand Canyon Hotel. So now the reincarnation of the Harvey Company is operating a railroad!

Illustration Credits and References

The sketch of the Harvey Girls near the top of this post was found at the hubpages.com website.

The next photograph was taken at the El Ortiz Harvey Hotel in Lamy, NM around 1912. It was found on the New Mexico History Museum website.

The following photograph was taken in 2004 at the grand reopening of the Santa Fe Depot in San Bernardino, California, where a group of original Harvey Girls made a costumed appearance. It was found on the San Bernardino Railroad Historical Society website.

The final illustration is a touching 2005 painting by Tina Mion, entitled The Last Harvey Girl. On her website, the painter comments: "Only a handful of Harvey Girls remain. Most live in the desert towns they once escaped to. One day soon, someone will be handed a cup of tea or coffee by the last Harvey Girl, and in an anonymous kitchen or living room an era will silently pass."

Monday, September 27, 2010

Puye Cliffs

Earlier this summer I toured the Puye Cliff Dwellings which are located near Los Alamos, about 35 miles northwest of Santa Fe. Puye Cliffs was the ancestral home of the people of Santa Clara Pueblo from the 900s until about 1580, when they moved to the Rio Grande Valley. According to pueblo legend, a black bear wandered through the village, harming no one, and led the people 10 miles away. Historians say the move to the river was occasioned by drought.

This site, now a National Historic Landmark, was closed from 2000-2009 due to flooding and erosion resulting from the Cerro Grande fire, which caused major damage to the Los Alamos area. It has only recently reopened to the public, and it was exciting to finally have an opportunity to visit this beautiful site.

We had a terrific tour by a member of the Santa Clara Pueblo who guided us up pathways and ladders from the bottom to the top of the mesa.

The cliff dwellings are on two levels with the bottom row about a mile long and the top level about 2,100 feet in length. Cliff marking are still visible like the one in the photo above. Many of these markings were the equivalent of directional signs.

The cliff dwellings are on two levels with the bottom row about a mile long and the top level about 2,100 feet in length. Cliff marking are still visible like the one in the photo above. Many of these markings were the equivalent of directional signs.

Paths and stairways connected the two levels and allowed residents to get to the top of the mesa where additional dwellings were located. The mesa dwellings were in the form of a multi-story complex built around a central plaza, though only crumbling walls (like those shown to the left) remain.

An interesting feature of the site is one of the original Harvey Houses. These were a chain of restaurants/hotels that serviced train (and later auto) travelers to the Southwest. There were more than a dozen Harvey Houses in New Mexico, though this one at Puye was the only one built on an Indian reservation. The mother of a friend of mine recalls dining in the Harvey House in Santa Fe when they took the train from California to Maine in 1931.

This site, now a National Historic Landmark, was closed from 2000-2009 due to flooding and erosion resulting from the Cerro Grande fire, which caused major damage to the Los Alamos area. It has only recently reopened to the public, and it was exciting to finally have an opportunity to visit this beautiful site.

We had a terrific tour by a member of the Santa Clara Pueblo who guided us up pathways and ladders from the bottom to the top of the mesa.

The cliff dwellings are on two levels with the bottom row about a mile long and the top level about 2,100 feet in length. Cliff marking are still visible like the one in the photo above. Many of these markings were the equivalent of directional signs.

The cliff dwellings are on two levels with the bottom row about a mile long and the top level about 2,100 feet in length. Cliff marking are still visible like the one in the photo above. Many of these markings were the equivalent of directional signs. Paths and stairways connected the two levels and allowed residents to get to the top of the mesa where additional dwellings were located. The mesa dwellings were in the form of a multi-story complex built around a central plaza, though only crumbling walls (like those shown to the left) remain.

An interesting feature of the site is one of the original Harvey Houses. These were a chain of restaurants/hotels that serviced train (and later auto) travelers to the Southwest. There were more than a dozen Harvey Houses in New Mexico, though this one at Puye was the only one built on an Indian reservation. The mother of a friend of mine recalls dining in the Harvey House in Santa Fe when they took the train from California to Maine in 1931.

Wednesday, July 14, 2010

Gunfighting in New Mexico

I'm currently reading a book about Victorian America (part of my 1905 research) and came across some interesting statistics about gunfights. From 1870-1874, New Mexico had the third largest number of gunfights in the U.S. (states and territories), behind Kansas and Texas. In the next five years, New Mexico was second only to Texas--with 23 gunfights in New Mexico in 1878 alone. In 1880-1884, New Mexico earned the dubious distinction of being #1 in the gunfighting derby.

I'm currently reading a book about Victorian America (part of my 1905 research) and came across some interesting statistics about gunfights. From 1870-1874, New Mexico had the third largest number of gunfights in the U.S. (states and territories), behind Kansas and Texas. In the next five years, New Mexico was second only to Texas--with 23 gunfights in New Mexico in 1878 alone. In 1880-1884, New Mexico earned the dubious distinction of being #1 in the gunfighting derby. The 1878-1881 period in NM was known for the Lincoln County War in 1878, and the Dodge City Gang which terrorized Las Vegas from 1879-1880. Several gunfighters from the gang headed out of town to Tombstone, Arizona after a vigilante party of townspeople was formed, though some returned to NM in the next few years. Billy the Kid, present for the Lincoln County War, was killed in Fort Sumner, NM by Sheriff Pat Garrett in 1881.

The number of gunfights in the US forms a neat bell curve--starting with 13 in the period from 1854-1859, peaking at 106 in 1875-1879, and dropping off to 9 by 1910-1914.

In 1908, for example, there were only four gunfights in the US--though two were in New Mexico. One of the remaining two was the fight between Bolivian soldiers and Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. (This was counted as a US gunfight since two of the protagonists were Americans.)

Still, I guess it's all in what you count as a gunfight. An 18-year-old boy was shot to death by a 16-year-old in the parking lot of the Santa Fe Place mall this week--a fight over a girl apparently. So it's not quite over yet.

Illustration Credits and References

Statistsics on gunfighting appeared in Almanacs of American Life: Victorian America 1876-1913 by Crandall Shifflett (1996); the author credits Encyclopedia of Western Gunfighters by Bill O'Neal (1979) for this data.

Other information from the Legends of America website.

Photograph of Billy the Kid's death marker courtesy of chucksville.org

Sunday, June 06, 2010

The White Sisters' Legacy

In April I was able to tour the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, a truly fabulous piece of property which houses this unique institution.

In April I was able to tour the School for Advanced Research (SAR) in Santa Fe, a truly fabulous piece of property which houses this unique institution.SAR got its start in the early years of the 20th century as the School for Archaeological Research, and it was headed by anthropologist Edgar Lee Hewitt from 1907 until his death in 1946. (He simultaneously headed the Museum of New Mexico after it was established in 1909.) SAR's mission was to train students, conduct anthropological research on the American continent, and preserve and study Southwestern culture.

Meanwhile, wealthy NY socialite sisters Martha Root White and Amelia Elizabeth White discovered Santa Fe in 1923. Both had graduated from Bryn Mawr, and served as Army nursing assistants during World War I. They found Santa Fe on a cross-country trip, and bought a large property here in the city. They built a home which they called El Delirio ("the madness"), and over the years the compound grew to include a kennel, guest houses, a swimming pool, and a variety of other structures.

El Delirio became a gathering place for artists, writers, and intellectuals, and the White sisters are said to have thrown some stunning parties in the 20s and 30s. Their home was the setting for lavish dinners, concerts, poetry readings, pool parties, plays, and masquerade balls.

El Delirio became a gathering place for artists, writers, and intellectuals, and the White sisters are said to have thrown some stunning parties in the 20s and 30s. Their home was the setting for lavish dinners, concerts, poetry readings, pool parties, plays, and masquerade balls. Five women, including poet Alice Corbin Henderson, second from left, display their costumes at the swimming pool dedication ca. 1926.

Five women, including poet Alice Corbin Henderson, second from left, display their costumes at the swimming pool dedication ca. 1926.The sisters also bred and raised Irish wolfhounds, and a cemetery for their beloved dogs can be seen on the grounds today.

Elizabeth helped to establish the Old Santa Fe Association, the Laboratory of Anthropology, the Wheelwright Museum, the Garcia Street Club, and the Santa Fe Animal Shelter--and all these organizations are still active.

The sisters were patrons and promoters of Native American Art and they opened the first Native American art gallery in New York City. Elizabeth was a founding member of the Indian Arts Fund in 1925, an organization which focused on buying up Indian pottery and other handcrafts to preserve these artifacts for future generations. She also served on the SAR managing board for 25 years.

The sisters were patrons and promoters of Native American Art and they opened the first Native American art gallery in New York City. Elizabeth was a founding member of the Indian Arts Fund in 1925, an organization which focused on buying up Indian pottery and other handcrafts to preserve these artifacts for future generations. She also served on the SAR managing board for 25 years.Martha died in 1937, but Elizabeth lived to be 96 years old. And when she died, in 1972, she left El Delirio and its remaining acres to the School for Advanced Research, giving that institution its first permanent home. That same year, the Indian Arts Fund also disbanded and deeded its collections to SAR.

The Resident Scholars' communal dining room--all set for delicious food and stimulating conversation.

The Resident Scholars' communal dining room--all set for delicious food and stimulating conversation.Today, SAR runs an advanced seminar series and a resident scholar program. The latter has provided over 160 pre- and postdoctoral scholars with nine-month residencies in which to read, reflect, and write up research results. A key part of the program is the unique intellectual interaction which takes place among scholars from different but related disciplines. Native artists have the opportunity to do residencies on site while they work on their art. SAR also houses the IAF collections and a state-of-the-art archaeological repository, and the SAR Press produces books on archaeology, anthropology, and Southwestern art and culture.

The grounds are beautiful, and a tour provides a look at SAR as it currently exists, and historical views of both SAR and the life of the White sisters.

The cemetery for the White sisters' Irish wolfhounds--each dog is identified by name.

The cemetery for the White sisters' Irish wolfhounds--each dog is identified by name.Illustration Credits and References

Photo of the White sisters' party at El Delirio courtesy of the SAR website (sarweb.org). All other photographs by the author.

Wednesday, April 07, 2010

Santa Fe Municipal Airport

When I first moved to Santa Fe, a couple of commercial flights were available from Santa Fe to Denver, but those were eventually discontinued. In June 2009, American Eagle instituted three flights a day--one to Los Angeles and two to Dallas. When a third flight to/from Dallas was added in February of this year, it became possible for eastbound passengers to make connections to and from Dallas, and I decided to give it a try.

The Santa Fe Municipal Airport is a charming step back in time. It was designed by noted Santa Fe architect John Gaw Meem, and constructed in 1957, in the southwest corner of the city. Its interior is full of southwestern accents.

It has one counter, one security line, one restaurant (The Airport Grille), one waiting room, and one gate. Parking involves writing a check for $3 a day for the duration of your trip and sticking it in an envelope in a box inside the terminal. "The Eagle has landed" heralds the arrival of the plane, and the gate agent greets arriving customers with a cheerful "Welcome to Santa Fe!"

Unfortunately, my travel experience was less than optimal due to weather-related interruptions at both ends (which caused me to miss my connection in Dallas and rerouted our return flight to Albuquerque due to wind, snow, and ice at the SF airport). But I am giving it another chance in May. It's so convenient--a 15 minute drive and no shuttle buses to the terminal required!

Photo Credits

The photograph of the terminal interior comes from the Veritas et Venustas blog by architect, urbanist, and author John Massengale. All other photos by Catherine Hurst.

Monday, March 08, 2010

Santa Fe School of Cooking

I had the opportunity a couple of weeks ago to attend a "bonus" class at the Santa Fe School of Cooking. The School is a 20-year fixture in Santa Fe, and its bonus classes, aimed at the locals, are test classes where the School and its chefs have an opportunity to try out new themes and ideas, and practice for the more formal (and more expensive!) classes come tourist season.

This was the third such class I've attended in the last couple of years--the first was a southwestern-themed brunch, and the second was a class featuring foods appropriate (by theme and portability) for tailgating at upcoming summer operas.

Our recent class featured four different kinds of chiles rellenos (stuffed chiles): cream cheese stuffed jalapeños in escabeche, New Mexican tempura rellenos, ancho chile rellenos, and chiles en nogada.

The last was my favorite. It featured a stuffing that included ground pork, garlic and onion, tomato puree, apples, peaches, plantains, dried apricots, raisins, and almonds. And as if that weren't enough, it was accompanied by a sauce made from pecans, almonds, queso fresco (or feta cheese), half and half, and sherry. The chiles were stuffed, lightly battered, fried, dipped in sauce, and topped with pomegranate seeds. Scrumptious!

Our chef for the day was Danny Cohen, ably assisted by Noe Cano.

And "class" is really not the right word for this experience--it's really a demonstration. The chef (who also teaches culinary classes at Santa Fe Community College) kept up an engaging patter while he cooked, and we could all see what he was doing in the reflection of the overhead mirror.

And "class" is really not the right word for this experience--it's really a demonstration. The chef (who also teaches culinary classes at Santa Fe Community College) kept up an engaging patter while he cooked, and we could all see what he was doing in the reflection of the overhead mirror. We students drank coffee and wine, took notes, and ate--a very easy assigment!

We students drank coffee and wine, took notes, and ate--a very easy assigment!I even learned a couple of new cooking facts/tips. For example, fresh jalapeños become chipotles when dried, and poblanos become anchos. And Chef Danny prefers the use of grapeseed oil for cooking (as opposed to canola oil), with olive oil only used to finish.

They do also offer hands-on classes, restaurant walks featuring private chef meetings and tastings in some of the best restaurants in Santa Fe, an onsite market for Southwestern foods and cooking tools, and one or two day team building seminars centered around the experience of cooking and eating together.

I highly recommend the Santa Fe School of Cooking, in spite of the steep price-tag ($70 and up for most classes). Visit in February and enjoy a "bonus" class!

Photo Credits

All photos in this post were taken by my friend and fellow student Linda McIlroy.

Monday, February 01, 2010

In Praise of the Sidecar, Part 2

Almost exactly two years ago in this blog, I wrote a paean to my favorite cocktail, the sidecar. I promised I would get to history (the sidecar's and mine) eventually. . . . In January I had a wonderful elderflower sidecar at McCormick & Schmick's in Boston which prompted me to get back to the rest of the story.

Almost exactly two years ago in this blog, I wrote a paean to my favorite cocktail, the sidecar. I promised I would get to history (the sidecar's and mine) eventually. . . . In January I had a wonderful elderflower sidecar at McCormick & Schmick's in Boston which prompted me to get back to the rest of the story.Generally accepted bartending lore assigns the origin of the drink to a time period near the end of World War I. The place was either London or Paris, and the inventor was an American Army captain who was driven to and from his local watering hole in the sidecar of a motorcycle. The drink was first mentioned in a bartender's guide in 1922, and 1934 was the first recorded recipe with a sugared rim (my preferred presentation).

Elizabeth Bowen, in The Death of the Heart (published in 1938), offers the cocktail to one of her characters:

Indoors, among the mirrors and pillars, they found Mr. Bursely and Daphne, cozy over a drink. Reproaches and rather snooty laughs were exchanged, then Mr. Bursely, summoning the waiter, did what was right by everyone. Clara and Portia were given orangeade, with hygienic straws twisted up in paper; Daphne had another bronx, Evelyn a side-car. The men drank whisky. . .

The cocktail was popular through the sixties, but faded in the seventies and eighties. Karen Kijewski, in her mystery novel Katwalk, published in 1989, laments their demise:

"Hey, Kat." I turned. "What's in a sidecar?"

"Huh? Oh. Brandy, Triple Sec, sweet and sour and lime--with a sugar rim and a cherry. Nobody drinks them anymore."

He grinned and waved and I waved back, at him and at the memories.

But by the 90s, cocktails in general were coming back in style; an article in the Boston Globe in 1994 describes the scene at a local lounge:

At the bar, the young couple put down their drinks--he with a cubana (sugar syrup, lime juice, aproct brandy, rum), she with a sidecar (Cointreau, lemon juice, brandy)--and step out on the floor to tango.

Another Globe article, six years later, is titled: "Sidecar cocktail rides again." A 2004 Boston Herald headline boasts that the "Sidecar takes back seat to no other cocktail."

And the cocktail was sufficiently mainstream to appear in a NY Times crossword in 2007.

I have been faithful to the sidecar since 1966, and in a future post I'll talk a bit about my history with the drink.

In the meantime, you can watch this video of Rachel Maddow shaking up a sidecar in a New York bar.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)