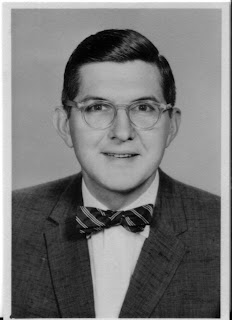

This is the eulogy I delivered for my father at his funeral service on August 23. Click here to read the full obituary written my brother.

We’re here today to celebrate the life of Robert Beyer.

My father was a great man—in many ways both public and private.

He was a great husband to my mother.

He meet Ellen early in their college careers at Hofstra, and she was the only woman he ever loved. He loved her deeply and devotedly until the day she died, and her passing left a big hole in his life.

He wrote her sonnets and love poems, washed the dishes and the kitchen floor, and never forgot her birthday or their anniversary.

He was a great father, and a proud and loving grandfather.

He set high standards for all of us—but was always there to support us when we faltered. He was the father of a son and three daughters—and my sisters and I so valued his quiet feminism—encouraging our college choices and our career options—always proud of our accomplishments—never expecting anything less or anything different because we were women.

My mother never drove, so my Dad chauffeured all of us to school and various other activities—I can remember him coming to pick me up after CYO dances—sitting outside in the car grading a stack of papers under the dim interior car light.

He was invariably up to date on the exploits of his seven grandchildren—as proud of the youngest’s coloring as of the older ones’ college studies and careers.

He was a great citizen.

He was always well-versed in the backgrounds of all the political candidates, and made careful voting choices. He served his country for years as a CIA contact for potential defectors among Soviet scientists—a secret he kept from us for forty years. He had come from a family of proud and vociferous Democrats and the autographs of Franklin Roosevelt and Adlai Stevenson hanging on the wall of his study were treasured possessions. I remember he cried when John F. Kennedy died—I had never seen him cry before, but JFK was an Irishman and a Catholic of his own generation.

A few years ago, when he was recovering from surgery, and in and out of consciousness, we asked him if there was anything we could get him. “Just get me a piece of paper that says George Bush is no longer president of the United States,” he said.

He was a great Catholic, and an incredibly ethical and moral man.

There was never, in our home, any expectation that we would not obey our parents, practice the golden rule, keep all our promises, be truthful on our taxes, share with those less fortunate, and go to Mass on Sunday. Dad was a lector for many years at St. Martha’s and here at St. Sebastian’s, and possessed a deep and unshakeable faith. He put his faith into action as a committed civil rights activist—traveling frequently to Tougaloo College in Mississippi in the sixties to support integration activities there. But he also demonstrated his faith every day by his language, his honesty, his behavior, and his genuine respect for every other human being.

His former pastor at St. Martha’s, Father Jude, told us on Thursday that he would see my Dad in Heaven. “And if he’s not there,” he said, “I don’t want to go.”

He had a great mind.

Growing up, I knew my Dad knew everything. He was never too busy to share, and he never talked down to us. A question to Daddy always went something like this. Me: “Daddy, why do I have these blue lines under my skin?” Daddy: “Let me tell you about the structure of the cardiovascular and circulatory systems.”

He had the intellectual curiosity of a child—always looking at the world through bright and shining eyes.

He could read and write in German, French, Russian, Latin, and a smattering of Chinese. He’s the only person I know who read Dr. Zhivago in Russian, and Proust in French. He edited the English language translation of a Russian physics journal--I can remember him sitting in his office at home, with an article in Russian in front of him, reading the English translation into a tape recorder.

He loved puns and wordplay. He loved opera and theatre and fine food and museums and world travel. He loved Sherlock Holmes and the New York Yankees.

He told jokes and stories with the Irish gift of gab—and it was always the right story for every occasion. A couple of weeks ago, I was working on some research about Eleanora Sears, an early 20th century long distance walker. I asked him on the phone if he knew who Eleanora Sears was. “Ah, Eleanora,” he said. “When I was a child, I had a primitive movie player and one of the film strips was of her walking from Boston to Providence in 1926—there she was, striding along.”

He wrote poetry for my mother, and wonderful speeches, and letters to his children that would break your heart. He could recite quotes from Shakespeare, baseball statistics, mathematical theorems, and the names of all the motels we stayed in our way to California in 1953.

He was a great teacher and mentor.

He was a full-time faculty member in the physics department at Brown for forty years, and part-time for another ten.

He advised and counseled generations of doctoral students—as with his own children, he established high standards for performance but was there with a helping hand, and some fatherly advice, if one of them was struggling.

But he didn’t just stay in the ivory tower. He also taught freshman physics, and used to cause quite a splash demonstrating principles of physics in a huge lecture hall—entering the room by riding a tricycle down an incline plane, or inhaling helium and starting his lecture with a chipmunk voice.

He taught courses for eight years at Laurel Mead where he lived since 1999. He started with a physics course, but wisely saw the limited appeal of advanced science in that setting, and moved on to his second great love—history. He taught a course in Russian history and a three-year course in the American presidency. He finished teaching a course in the Civil War less than three weeks ago—and told us it would be his last—it was getting too hard for him to lecture. I firmly believe his love of learning, his sense of duty, and his commitment to his students enabled him to complete that effort.

He had a great will and a great spirit.

His heart was damaged by two bouts of childhood rheumatic fever. He was tutored at home through high school because he was too sick to go to school. He wasn’t supposed to live to be 21, but his spirit and will always more than compensated for his weakened body. Though he suffered from damaged heart valves, multiple sclerosis, a lost kidney, and a variety of other ailments, he never ever complained, and was always ready with a joke or a quip about his situation. He came back from near-death so many times over the years that we somehow believed he would never die. His determination and his will to live—to do what he needed to do to make it back—were mind-blowing.

And he was a great physicist.

His doctoral research at Cornell was classified by the U.S. Government for years after he received his degree, so he had to start a whole new line of study. During his career he wrote four books, co-wrote three others, translated or edited several more, and authored more than 75 scientific papers. He finished his last book, The Sounds of Our Times, a history of acoustics, when he was nearing 80. A reviewer had this to say:

"To produce a coherent and enlightened summary of two centuries of work in any science requires a very special person: One who not only understands it all, but who has taught it all, and has personally contributed to its development; one with the patience and scholarship to research it all, historically and technically. Such a person is Robert T. Beyer. No wonder the resulting book is so remarkable and informative. A very hard-to-follow world class act.....”

I believe he was a man who had no regrets about the way he lived his life—as a husband, a father, and a grandfather; as an American; as a Catholic; as a teacher, mentor, and colleague; and as a truly good man.

And now that glorious mind, and that mighty spirit, are free from this mortal coil, and can join my mother again, and forever. And I say to him what my brother and sisters said to him often in these last few years:

Bye, Daddy. I love you.