Photo courtesy of Fisk University

Photo courtesy of Fisk UniversityThis is a tale of what I consider to be very bad behavior by the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe.

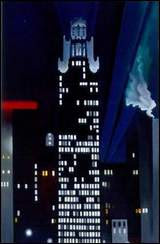

In 1949, Georgia O'Keeffe divided the art estate of her late husband Alfred Stieglitz among a number of institutions. One of the recipients was Fisk University, a historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee. The school received 101 paintings from O'Keeffe including her own Radiator Building--Night, New York, painted in 1927, and a number of other valuable works.

Like many small private colleges, Fisk has struggled financially in recent years. Protection and display of the valuable art collection was always an issue--O'Keeffe paid to send the entire collection sent to New York for restoration in the 1970s, and before her death donated tens of thousands of dollars for maintenance of Fisk's Van Vechten Gallery and the donated works.

But the gallery was a building constructed in 1888 and formerly used as a gymnasium; the college was no longer able to guarantee protection of the works there and the paintings were put in storage at the Frist Center for Visual Arts in Nashville in November 2005.

The following month, Fisk sought to sell Radiator Building, its most valuable painting, along with Painting No. 3 by Marsden Hartley. The sale of these two works would, the college believed, allow it construct a new science building, make needed campus repairs, replenish its hemorrhaging endowment, and appropriately protect and display the other 99 pieces of art, which include works by Picasso, Renoir, and others.

Listen to the details in this 2005 NPR story.

Shortly afterwards, the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe stepped on stage in this deal. The Museum got involved by virtue of the dissolution of the O'Keeffe Foundation in May 2005; the Foundation turned over all its assets to the Museum and asked that the Museum "step into its shoes" to protect the Stieglitz gift to Fisk. So the Museum started legal action to block the sale of the paintings, stating that Fisk was violating the terms of O'Keeffe's gift to the school.

And the Attorney General of Tennessee also became a party to this deal, representing the people of Tennessee, for whom these works were characterized as a cultural asset.

Christie's had appraised the O'Keeffe for $8.5 million in 2005, and the O'Keeffe Museum offered Fisk $7 million for the painting. A Tennessee judge gave the school 30 days to see if they could get a better offer that would allow them to keep the work in Tennessee. The judge eventually nixed the deal with the O'Keeffe Museum in April 2007. Several offers of $20 million or more had been received for the painting at this point, although none met the "undisclosed requirements negotiated between the university and the Georgia O'Keeffe Museum." But clearly $7 million was not a good deal for Fisk and Tennessee.

By August of this year, the Museum had agreed to drop the lawsuit, buy Radiator Building for $7.5 million, and give Fisk "permission" (how does that work?!?) to sell the Hartley on the open market. The Museum also agreed that if they sold the O'Keeffe within 20 years they would give Fisk half of any profits (wow--what generosity! And how do they get to sell it if they won't let Fisk sell it?), that they would lend the painting back to Fisk for 4 months every 4 years, and give them a high quality reproduction to use in the meantime. In wonderful lawyer-speak, the Fisk attorney noted that this was "not a sale--just a lawsuit settlement".

Photo courtesy of Marshall/Star Telegram/SIPA

Photo courtesy of Marshall/Star Telegram/SIPABut while the settlement agreement was pending, Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton offered Fisk a new deal. She would give them $30 million for a 50% stake in the entire collection. The works would be displayed half-time in the new Crystal Bridges museum she is building in Bentonville, Arkansas, and at Fisk the other half. The terms of the offer would also include $1 million for Fisk to renovate and upgrade their art gallery, as well as an art internship for a Fisk student. This seemed to me to be a real win-win offer--Fisk would get the money they needed, the paintings would stay in the South, the collection would be kept intact, and Fisk and the citizens of Nashville would have access to the paintings half the time. (This is in contrast to no access, which is the current state of affairs, since the paintings are in storage and not on display.)

With the Walton offer on the table, a Nashville judge vetoed the O'Keeffe Museum offer as detrimental to the interests of the people of Tennessee.

Photo courtesy of US Department of Energy

Photo courtesy of US Department of EnergyIn October, the O'Keeffe Museum asked that the Tennessee judge block the deal with Walton. This was clearly not good news for Fisk. According to a 10/17/07 New York Times article by Theo Emery, "Fisk's president, Hazel O'Leary, said the university was being 'held hostage' by the litigation. 'Their intention is to bleed us to death,' she said. 'They know that time is not on our side here.'"

The O'Keeffe Museum now wanted (are you ready for this?) the entire collection removed from Fisk's control and sent to New Mexico.

1950 photograph by Carl Van Vechten, for whom the Fisk art gallery is named.

1950 photograph by Carl Van Vechten, for whom the Fisk art gallery is named.So what would Georgia O'Keeffe do? This seems to be at the heart of the various legal arguments. A trial is scheduled for February to decide whether Fisk's agreement to share the collection with Walton's Crystal Bridges (which is scheduled to open in 2009) is close enough to O'Keeffe's wishes to be approved.

On Tuesday of this week, Tennessee Governor Phil Bredesen weighed in on the issue. According to an article in the Tennessean, he is quoted as saying: "As a businessperson, I would be very concerned at the deal Fisk has cut with the museum in Arkansas." Bredesen says that estimates from art experts and insurers indicate the collection "could easily be worth $150 million. And $30 million for half of it is not a very good deal."

Crystal Bridges executive director Bob Workman says the price reflects the restrictions placed on the collection by O'Keeffe. "This is a creative, long-term way to satisfy Ms. O'Keeffe's demand that the collection remain intact, to provide needed funds for Fisk University and to keep this historic collection in the public domain."

Amen to that, I say. Fisk says that they may have to close in 2008 if the deal is not approved. They have mortgaged all of their buildings and other loan options have been exhausted.

Imagine how much money has been spent by lawyers on this case over the past two years--probably enough to keep Fisk open for a number of years to come. And it is hard for me to imagine that Georgia O'Keeffe would have wanted Fisk to close, or would have approved her namesake museum's attempt to hijack the work(s). In a 1949 article in the New York Times at the time of the original bequests from Stieglitz's estate, she stated that "after 25 years, the (pictures) can be sold if the institutions have no further use for them." What's not clear about that?